Episode 11: Feeding the World in Style

How a human-scale food system can feed 10 billion people on 97% less land than we use now, with higher quality and social justice than the world has ever known.

◄ |

![]() Home |

Listen |

Watch |

Design |

Map |

Join |

►

Home |

Listen |

Watch |

Design |

Map |

Join |

►

Transcript

Could you grow all the food you need to survive?

Intro [music]

The Big Lie of agriculture

Subsistence Farming For Billionaires

What’s Wrong with Market Gardens?

Farm-to-Table Advantages

Block-to-cafe advantages

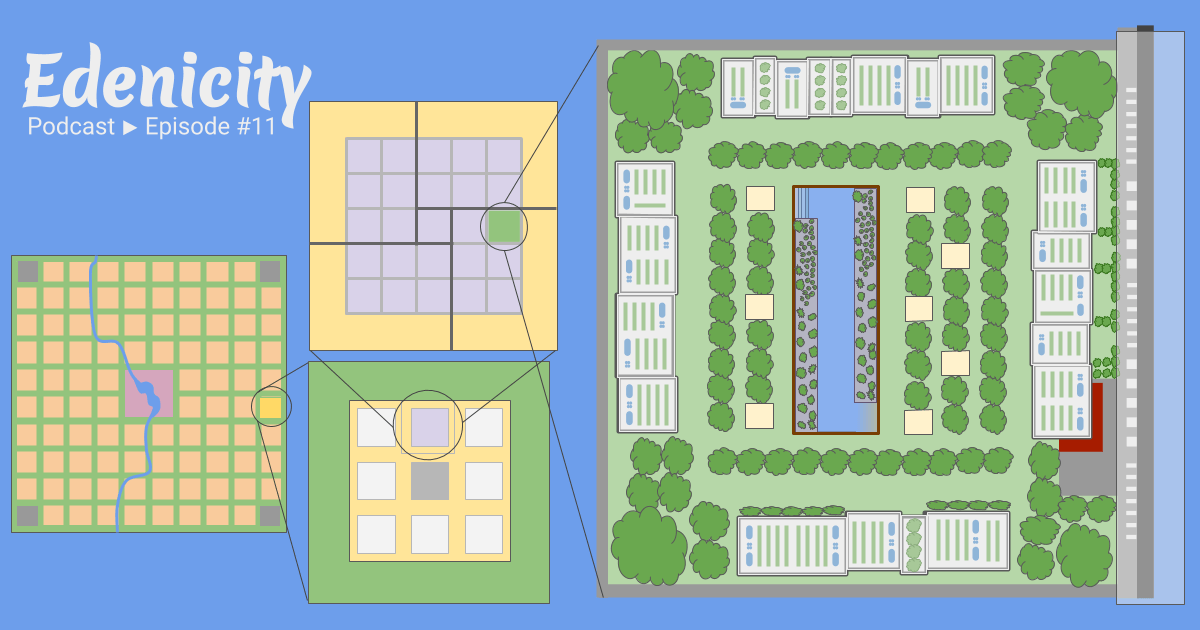

Tour of Edenicity food system

Zone 1: Rooftop gardens

Zone 2: Courtyard orchards

Zone 3: Broadacre village crops

Zone 4: Forest belts around towns

Zone 5: Wilderness

Role of automation

Social distancing (epidemics)

The sixth function of design

Close [music]

Sources

▲ Could you grow all the food you need to survive?

Do you know how much space you would need? How much material and equipment would you need? What would it cost? How much time would it take?

As a former market gardener, let me set the record straight: subsistence farming is hard. It takes a long time to learn, and it takes skill and capital. Worse, as any economist will tell you, doing it all yourself is a ticket to poverty, renouncing as it does the benefits of specialization.

But what about the other extreme: feeding the world? What comes to mind? Do you picture giant fields stretching past the horizon? Combines and harvesters with wheels as big as houses? Huge warehouses full of chickens, pigs, roaring machinery, hundreds of workers rushing around in the dusty half light with baggy clothes and sharp tools: killing, cutting, cleaning, sorting, drying and bagging?

For the past 70 years in the United States, most schoolchildren have watched films, draped in the language of science, explaining how the inefficiencies of subsistence farming can't keep up with the growing world population. The situation, we're told, is getting more dire every day, so apparently the solutions must become ever more extreme until the only thing efficient enough to feed 3, 6 or even an unimaginable 8 billion people is ever more gigantic, mechanized, noisy, smelly and terrifyingly inhumane agriculture. "Got a problem with that? Shut up!" we're told. "your life and everybody else's depends on it."

But... what if this whole picture is wrong? Not just wrong, but exactly backwards.

In Episode five, I observed that the second function of design is to resolve false dichotomies. What if industrial versus subsistence farming is really just another false dichotomy? Not just that, but also, when it comes to food, big versus small, local versus global, specialized versus not, mechanized versus not.

What if the world's food system is ripe for redesign? And what if it turns out that the designs that shatter these dichotomies look like the most beautiful greenhouses? The prettiest kitchen gardens, the most glorious orchards, the most refreshing swimming holes, family farms or forests you ever saw?

▲ INTRO [music]

Cities designed like modern Edens for economic and ecological abundance. I'm Kev Polk, your guide to Edenicity.

Welcome to Episode 11 where we'll take a deep dive into the edenicity of food production.

▲ The Big Lie of agriculture

Let's start out by calling out the big lie of agriculture: that you must "go big or get out." That's a direct quote from Earl Butts, Secretary of Agriculture under Richard Nixon in 1971. It's shaped agricultural policy in the United States ever since, and it's a plausible idea, deriving as it does from the very real industrial phenomenon of economics of scale.

The idea is, if you have to make just one of something, say, a screwdriver or a canned beverage, it's very expensive. We're talking thousands of dollars. But if you make millions or billions of them, you can learn a great deal about the process, streamline the tooling, and bring the cross down to a buck apiece or less.

The problem is, crops are living things and therefore subject to the ecological principle of interdependence. In Episode two, I mentioned how it's rare to find an ecosystem that remains stable when any one species has exclusive use of more than 2% of the energy and resources.

Maintaining many square kilometers of a single crop, as big farms do today, is an obscene violation of that law. Think of the landscape is a massive quilt of niches or opportunities for different species to thrive. Every undulation in the land, every layer of soil or tiny variation in soil chemistry, every nook or cranny in the foliage, every open space, no matter how small, creates its own microclimate. No single species can fill them all. When these niches remain empty, the surrounding ecology will do its best to restore the balance. Its tools? Those detritovores and pioneer species that we call pests and weeds.

Therefore, it should come as no surprise if we discover that smaller farms, which typically grow a wider variety of crops and cause less of a disturbance, are more efficient at growing living things than the big farms. The data agree. GRAIN, an international rural nonprofit, crunched the land use numbers from the United Nations and various world government agencies. On May 24th 2014 GRAIN.org released a report titled Hungry for land: small farmers feed the world with less than a quarter of all farmland. GRAIN found that subsistence farmers and small scale family farms still feel 80% of the world, and they do it on 24% of the farmland. Depending on in the region, that works out to about 2 to 6 times the yield of commercial farms.

This is not new news at all. More than a century ago, in 1909, Franklin Hiram King, an accomplished professor of agricultural physics at the University of Wisconsin Madison, spent 9 months touring and assessing land practices in Southeast Asia. He wrote up his travels, which his wife, Carrie Baker King, published after his death in 1911. The book was originally titled Farmers of 40 Centuries or Permanent Agriculture in China, Korea and Japan. But it was rereleased in an unabridged 2004 Dover edition under the title Farmers of 40 Centuries: Organic Farming in China, Korea and Japan.

I like the original title better. Of course, I would, as permanent agriculture is the etymological root of permaculture, which I'm twice certified to practice. A lot of what I'll be talking about today is straight up permaculture.

Among other things, Professor King was concerned with conserving soil and soil fertility, which American settlers had degraded noticeably in just a few hundred years. By contrast, Asia had fed a lot more people on a similar amount of land for more than 4,000 years. On page six of his book, King writes: "Nearly 500 million people are being maintained chiefly upon the products of an area smaller than the improved farmlands of the United States. Complete a square on the lines drawn from Chicago southward to the Gulf and westward across Kansas, and there will be enclosed in area greater than the cultivated fields of China, Korea and Japan and from which five times our present population are fed."

▲ Subsistence Farming For Billionaires

Subsistence farming is a fact of life for billions of people to this day. But weirdly enough, it's not just the poor who think about it. Survivalism has long been a popular hobby in the tech world. It gets more intense at the high end. When Team Human podcast host Douglas Rushkoff was invited to consult at a conference of billionaire hedge fund managers in 2017, he found them obsessed with emergency bunkers and what to do if civilization collapses and their money loses its value. He wrote an article about it in onezero.medium.com and 2018 with the title "Survival of the Richest. "

Remember, these are the guys (yes, almost entirely guys) who are making the biggest investments in every industry, including agriculture. Now I'm not against an opportunity structure that can create billionaires, at least temporarily. See Episode 8 for more about that. To paraphrase from that episode, money has more value when it circulates. Right now, though, interest rates are as low as they are, in part because the world is awash in savings. The money is just sitting there, and that's a design problem to be solved.

Still, for the billionaires who are listening (you know who you are!) let's answer some of those questions about growing your own food. According to Joel Salatin, author of You Can Farm, it does take years to learn. According to David Duhon's book One Circle, published by Ecology Action in 1985, you can grow a complete diet for one in 100 to 400 square meters, but it won't be easy. You'll be using bio intensive gardening, which involves double digging 100 to 400 square meters of garden beds per person. I've only ever prepared 40 square meters using that method, and I don't ever want to do it again. It's back breaking work. So, Rich Bros, Take Rushkoff's advice and be good to your staff! Treat them like family, because nobody else will work that hard for or with you if money should lose its meaning.

▲ What’s Wrong with Market Gardens?

Now that I've sung the mixed praises of small farms, let me also point out some of their limits as practiced in the United States today.

Of course, everybody loves a farmer's market. In Athens, Ohio, it's the cultural event of the week: a pageant of produce, a place for commerce and stories and recipes and gossip, a celebration of everything wholesome and quirky.

When I started bringing my produce to market by bike, my hippie customers shied away. I was getting too weird for them, but old timers loved it and started buying all my Kentucky Wonder beans and iceberg lettuce, week after week, swapping recipes, even trying my Thai basil and lemon cukes.

If you're an old enough market goer, you probably remember that moment when farmers markets won you over. It was a tomato, wasn't it? A giant, juicy heirloom beefsteak tomato with a fancy name like Hungarian heart. Or maybe a tiny super sweet Sungold. These are truly cultural artifacts, as delightful and shiny as any crown jewel.

The problem is, it's quite common for market gardeners to sell only half of the delicious produce they grow. When there's a glut of beans or lettuce or blueberries or, yes, tomatoes, even farmers with the better marketing, longevity and customer loyalty end up donating to a food bank at the end of the day. Some growers create value added products such a squash bread, barbecue sauce, jams, puddings, muffins. The list goes on. Been there, done that! These sell well and bring in extra money. But they take way more time to make than it takes to plant and pick.

And you're competing with supermarket prices, meaning products that used a lot of automation in their production. As cybernetics pioneer Norbert Wiener pointed out in 1948, automation is a form of slave labor, and competing with it ultimately means working like a slave.

The other problem with market growing is the market and the place where you grow are often far apart. You have to pick, clean, pack, drive many miles, unpack, sell, repack, drive home and re purpose whatever didn't sell.

What are the alternatives? Some growers create a CSA. That stands for Community Supported Agriculture, where they find out what people want to eat, grow it and let them come pick it up every week. That's better, but still inefficient. How many people have joined a CSA dreaming about tomatoes, fennel and leeks—only to find their bags stuffed with kale and just a handful of other items week after week? And you still have a lot of people driving to the pickup point and pouring carbon into the atmosphere. The economic answer is to specialize. With wholesale co-ops, full time retailers and professional freight services, growers can stay home and do what they do best, and customers don't have to make a special trip. But this much specialization requires a denser population than we ever had in Athens, Ohio.

▲ Farm-to-Table Advantages

Another approach is to integrate a farm with a restaurant. This has several advantages. First of all, there's a guaranteed market for the produce. The chef works in conjunction with the farmer to plan a season's worth of menus and of growing. There's far less waste. First of all, there's a lot less transportation if the farm is close to the restaurant. There's much less packaging because you're moving things in larger quantities in bulk, and so the surface area to volume ratio is smaller. The packages are larger, and if you add up the area of one large package versus a whole bunch of smaller ones, the larger package has less material. The compost from the restaurant can be reliably captured for use on the farm, as a natural part of that partnership. And waste water from the kitchen can even go back to the gardens if the climate dictates and the gardens are close enough.

▲ Block-to-cafe advantages

But Edenicity takes this one step further. In the Reference Design, which you can download from the news link at edenicity.com, you'll find that every block in the city grows most of its own food and serves it up in its own cafes. As is common in many parts of the world, Edenicity would be designed for people to get most of their meals at a cafe, pub, diner or restaurant within easy walking distance. This is also consistent with a long, gradual trend in the United States for each succeeding generation to cook less at home.

Edenicity would have 2 to 4 cafes per block, providing something like 34 jobs: six back of house staff, eight wait staff and maybe 20 agricultural workers. Private kitchens in the households would be, correspondingly, that much smaller.

This would be great news for climate refugees and subsistence farmers moving to the city. This is a skilled workforce. Their growing skills would be welcome on every block, and they wouldn't have to huddle in peripheral shanty towns that many urban migrants have to endure today, scrounging in town for menial work that requires a long commute.

▲ Tour of Edenicity food system

Let's take a tour of the Edenicity food system. This system is organized by permaculture zones. The concept is areas that need the most frequent attention with the highest yields are closest to where people live and eat. There are five zones ranging from Zone 1, right where you live, to Zone 5, the unmanaged wilderness between cities.

▲ Zone 1: Rooftop gardens

We'll start with Zone 1, rooftop gardens. Because this is the most intensive zone, this is also going to be the most detailed part of today's podcast.

Each row of five or so houses would share a common roof with some combination of agriculture, greenhouses and shade houses. These are the most productive part of the food system, and they require the most attention: about two full-time workers per roof. I'm pulling my labor numbers from Julie Marie Simonetti’s 2015 Master's thesis from the University of Florida.

Now I'm not a fan of high rise farms. In natural soil, it costs something like $5 per square meter to prepare a site for farming. A high rise floor across $1,000 to $1,700 per square meter to build. You would need 200 to 300 times better productivity than field agriculture to make that pay.

Actually, the craziest thing I ever saw was a drawing of underground farming beneath the skyscrapers in the Cities issue of National Geographic, April 2019. I mean, you have the cost of excavation or tunneling, then installing LED lights, air pumps, water pumps and the ongoing cost of electricity for lighting. If you powered it with solar, your solar panels would take up about 20 times the area of that underground farm. Bad idea! No, for a long time to come, most of the physical space dedicated to farming will be in some facsimile of natural soils under an open sky.

But a rooftop garden is an exception. The building needs a roof, but most roofs, at best, just look pretty and keep out the weather. So let's apply the fourth function of design from Episode 5: design factors redundancies. In other words, let's think about what else a roof can do. Well, it's exposed to all this light from the sun. What if we could use that to grow stuff? And, depending on climate and season, a simple roof can quickly add or steal heat from the building. But a greenhouse or a shade house could moderate these extremes, as I'll explain in a moment. Think of it as a hat for your building: keeping the heat out or holding it in is needed. This factors out some of the climate control a building needs. In other words, it makes air conditioning and heating work better.

In cool and temperate climates, the roof would have a transparent covering probably ETFE: ethylene tetrafluoro ethylene. ETFE is the same plastic you'll find on the Eden Project in Cornwall, England, the Beijing National Aquatic Center, the Banc of California Stadium in Los Angeles and especially the experimental media and Performing Arts Center in Troy, New York. ETFE lasts decades, and it is recyclable.

Under the ETFE cover, we can install an aquaponics system that uses fish to fertilize plants grown in water rather than soil. This approach recirculates water, reducing water demand—when you compare it to field crops—by factors of 10 to 50. The produce is not exposed to mammal contaminants such as E. Coli in the way that field grown food is, which factors out laborious cleaning. The roof's location makes the produce far more accessible to cafe kitchens below and keeps the processing and transport simple. This factors out the heavy equipment such as tractors, cleaning stations, conveyors, trucks and so forth that you would need for field crops, though you might need an elevator.

Now, you might wonder what the fish eat. Right now, the standard is commercial fish food, and organic is available in bulk today at $6 a kilogram. According to National Geographic, a kilogram of feed produces nearly a kilogram of fish. This is possible because a good chunk of the fish's weight is water and carbon from the atmosphere. But that same kilogram of feed would give you only half as much chicken, three times less pork or seven times less beef. Even so, the fish costs more than it would earn wholesale. But for each kilogram of fish, you also get 15 to 30 kilograms of vegetables. The overall yield is about 20 times better per square meter than field agriculture (here I'm using numbers from friendlyaquaponics.com), so the cost is comparable to that of a normal roof plus an aquaponics greenhouse on the ground.

So for free, you gain convenience, factor out a lot of heavy equipment and factor out some climate control for the building. Let's examine that last item, climate control, in detail.

In the winter, the greenhouse roof would hold heat in during the day, giving it time to seep into the building and the water tanks. Water is several times better at storing heat than, say, rock. At night, the ETFE cover would dramatically slow heat loss from the growing tanks and the building (for you physics majors: it dramatically reduces convective losses and somewhat slows the radiative losses). As a result, the building spends significantly less energy on climate control, perhaps more than the energy required to run the air and water pumps. This is a classic wealth strategy of multiplying the value of imports—in this case solar energy—that I mentioned in Chapter 10.

In the summer, the greenhouse can have a shade cloth or act as a solar chimney, pulling air through buried tubes into the building and out through high vents in the greenhouse. Or it could blow hot air through insulated ducts down into a buried thermal mass with a cold air return. Again, any of these strategies employs the ecological wealth strategy of multiplying imports through reuse. So the output of this, per the Reference Design, is 1 to 2 kg (or 2 to 4.5 pounds) of greens, grains, or veggies per resident per day. The aquaponics tanks use fish to fertilize the plants, producing 50 to 70 grams (or 2-3 ounces) of fish per resident per day.

In dry lands, the roof and walls would be designed with trellises and dense vines to keep the building surface shaded. Beneath these, intensive annual crops could be tended in planters with buried drip irrigation—no surface watering at all. In humid, hot climates the roof would have an 80% opaque, reflective top and be open to breezes on all sides, with insect screens. This limits growth to greens and other shade tolerant crops. But Zone 2, which we'll get to in a moment, will more than make up for that.

The next 3 zones are a lot less intense, so I'll spend less time describing them. The plantings in Zones 2 to 4 are a combination of personal experience and my notes from Geoff Lawton's online Permaculture course.

▲ Zone 2: Courtyard orchards

In Edenicity, every city block would manage its own Zone 2. Main growth would happen in a large outdoor courtyard between the buildings. You would also find plenty of food production in hedges and tree plantings between the buildings and the walkways and bikeways. A team of eight on-site professionals would maintain these gardens and systematically harvest produce, so none goes to waste. Even so, there would be plenty available for residents to snack on at will during the growing season.

Now, as I describe these gardens in detail, imagine being a child in this Eden-like landscape that literally feeds you without effort.

In cool and temperate climates, you would have orchards and hedges of mixed species for mutual support: legumes to fix nitrogen, plus apples, peaches, plums, cherries and nut trees with grapes climbing arbors and trellises within easy reach of several picnic shelters. Many blocks would feature natural swimming ponds. These are gaining popularity worldwide. They would buffer storm water, build soil faster than any other method (although you would need to dredge them to adjacent gardens from time to time), and they can produce an incredible amount of food, such as rice, wild rice or watercress. The ponds would use native fish for mosquito control. A Purdue Extension report found that well maintained ponds can cut mosquito populations by 90% or more. Shrimp and snails would clean the algae, and native submerged plants would provide aeration. For swimming purposes, the ponds offer clean, fresh water without chlorine. Of course, they would require monitoring, with backup ultraviolet disinfection if needed.

Now, in humid, hot climates, that center courtyard would feature large trees such as jackfruit, breadfruit, mango and Brazil nut with an understory of large bushes such as coffee and cocoa. In an understory, these plants yield less but last a lot longer and require much less maintenance than they would if grown in large, open field crops. You would also have vines from tropical yams climbing the trees. In the front, between house and street, you would interplant bananas and papayas, sugar cane and climbing yams in two meter mulch pits. Everything gets as much coarse woody mulch as possible. According to Geoff Lawton, who runs the Permaculture Research Institute in New South Wales, Australia, the banana circles consume half a cubic meter of mulch every 10 days. Rot is an issue, so you would need to keep the trees open at ground level for air circulation. Natural swimming ponds would also thrive in hot, humid climates, with really great year-round food production, including taro.

In drylands, though, there would be no swimming ponds at all. In the courtyard, you would have high, salt tolerant trees such as date palms, mulberry, fig, pomegranate. Along the walkways and bikeways, you would plant citrus. The high tree layer provides shade for small, sunken bed gardens with buried drip irrigation. You would catch and store runoff in large cisterns.

▲ Zone 3: Broadacre village crops

Let's move on to Zone 3, which surrounds each village of 25 blocks or 6,000 people. This is a 250 meter wide strip that looks a little more like a modern farm. Here you'll find your broad acre crops (such as corn, wheat, rice, soy), local super crops (such as quinoa and wild rice), and stands, rows and hedges of low maintenance trees, as well as ponds and rotational grazing for cattle and chickens. The cattle graze the grass and browse fenced off forest edges for a few days at a time before being moved on. Then compost piles are made in the field from grass clippings, kitchen scraps and manure. Chickens raid these for bugs, turning and aerating the compost piles in the process. Done right, these chickens don't need feed, and the compost is soon ready and enriched in phosphate for garden crops. After the chickens are moved, you plant your broad acre crops, and they do well because the chickens have removed many potential insect pests.

Zone 3 fills in the dietary gaps for staple crops, plus, if so desired, at least 20% of the animal products you would find in the typical American diet. The animal rotations also builds soil, though not nearly as fast as the Zone 2 ponds. Zone 3 would draw about three workers from each block, providing about 75 local jobs for each village of 6,000. That's how it would work in a cool or temperate climate.

Now, in hot, humid climates, there would be no animal grazing at all. Tropical soils are fragile, so animals must be penned and fed cut forage with manure removed to compost piles as I just described. The main feature here is large aquaculture systems, combining fish, rice, taro and waterfowl such as ducks in terraces or in a series of narrow ponds between mulch pit gardens. These are highly productive year round and would probably outperform the Zone 1 roof gardens.

Now, in dry lands in Zone 3, you would have tree belts on swales, and these are the contour irrigation ditches that concentrate water that I mentioned back in Episode 10. The tree belts provide enough shade and wind protection for broad crops grown in the rainy season, and you could rotationally graze the area in between with tight-packed animals, building soil. This is the Allan Savory Method mentioned back in Episode 10.

▲ Zone 4: Forest belts around towns

Zone 4 is a 760 meter wide forest belt surrounding each town. That's, like, half a mile wide. Recall that in Edenicity, each town includes 9 or so villages of 6,000 with a total population of about 50 to 60,000 people. While the Zone 4 forest would definitely be a pleasant place for a walk, it's not wild, like Zone 5 that surrounds the city. Zone 4 is farm forestry with a mix of timber species. These supply edible fruit and greens and mushrooms. The trees are thinned annually for vigor and harvested selectively starting at about year 25. It would establish and grow up to twice as fast as natural forests in a given climate because the ground would be prepared with earthworks such a swales, the occasional large water feature and careful succession plantings, meaning an over abundance of pioneer species such as nitrogen fixers. You thin these periodically during the first five years to provide mulch and growing room for the productive trees. The big picture here is to keep all available niches filled with support species and productive trees from day one.

Now, Zone 4 would be a place of absolute delight and rejuvenation. Some of my happiest memories are playing in tropical ponds and waterfalls, picking mango, passionfruit and strawberry guava in the semi wild woods. More recently in the woods near my market garden in Ohio each spring, I looked forward to harvesting ramps (which is a garlicky spring green) and chanterelle mushrooms in late summer. In Edenicity, this lifestyle would be more deliberately productive and accessible. Zone 4 would be less than a six minute bike ride from any home.

▲ Zone 5: Wilderness

Zone 5 is the wild area beyond the city. In all likelihood, these are lands previously damaged by large scale crops or overgrazing, perhaps for many generations. Restoring it may involve removing toxic waste, then a few decades of successional plantings or grazing. They should be designed to pay for themselves with some economic returns. Depending on the climate and the location, this could look like Allan Savory's tight-packed cattle grazing strategy or the Caribbean pines that provided valuable resin and habitat in Gaviotas, Colombia, as I mentioned in Episode 10: Greening Urban Deserts. But the goal for Zone 5 is to reestablish wild, diverse native habitats as soon as possible so we can end the mass extinction.

Zones 4 and 5 would employ upwards of 225 people per town, or 22,500 people altogether per city. The roster would include permaculturists, hydrologists, foresters, ecologists, logistics experts, arborists, cattle handlers, machine operators, planters, loggers and foragers. For the first five years or so, 90% of their efforts might focus on Zone 4 in town and 10% in Zone 5 in the surrounding region. Then, for the next couple of decades, the labor might split more like 50/50 between zones 4 and 5. If you're moving to the city from subsistence farming or herding, these jobs, along with Zones 1 to 3, provide a generation of good jobs that build on your existing skill set. Now, over the course of a couple of decades, as Zone 4 matures and Zone 5 gets restored to healthy wilderness, a city of five million might lose about 11,000 agricultural jobs. But this gradual loss would give people time to learn new skills, and there would still be some 440,000 absolutely steady agricultural jobs per city in Zones 1-4.

▲ Role of automation

Eventually, though, some jobs in Zones 1 and 2 will no doubt be displaced by automation. I'll give you an example. I know from experience how labor intensive it is to keep birds out of your blueberries. Netting is a lousy solution. I've had to free snakes caught in it, and birds tend to snare their feet in the nets, too. It's demoralizing. I've even gone so far as to encase individual baughs in row cover fabric, which keeps out the birds without collateral damage. This gives great yields, but it's very labor intensive, and I've seen wild birds plunder tree crops like apple, peach, cherry and especially serviceberry, a delicious and prolific springtime tree fruit, to the point where they're just not viable crops. Remember, Zone 5 provides plenty of wild habitat, so wild birds will not go extinct if we exclude them from our gardens. Short term, the humane solutions are labor intensive and happily provide jobs for those moving to cities from subsistence farming (Episode 8 describes just how vast this trend really is), but long term, I'm sure we'll see swarms of small drones picking berries or applying and removing fabric covers.

If we're not careful, these could cost not only jobs but mental health. To offset the lost jobs automation should be, at the very least, subject to an asset tax that directly returns value to people via universal basic income.

As for mental health, UK studies in 2004 and 2007 suggests that inhaling the soil bacteria mycobacterium Vaccae stimulates the release of serotonin and possibly other beneficial neurotransmitters, both in humans and rats. Actually, I'm guessing it's true for dogs, too, as my crazy shepherd-chow mix used to spend hours with her snout jammed in gofer holes snorting and snuffling like an addict.

Anyway, the researchers found that the soil bacteria lifted people's mood and cognitive abilities. Zoe Schlanger provides a nice summary of these findings in qz.com, also known as Quartz, May 30th 2017.

So if we do automate agricultural work, we need to do it in such a way that it doesn't prevent children and adults from picking fruit or digging or playing in the dirt.

▲ Social distancing (epidemics)

One more thing. When you go to Edenicity.com and download that reference design, you'll notice that there is more than twice as many people per square km as the typical American city such as Columbus. Does that make you uneasy? As I record this, we're still in the early days of lockdown and social distancing as part of the coronavirus epidemic. I went to the grocery store this morning and was so glad it wasn't crowded. The checkout clerk screamed at me to unload my groceries as far as possible from the person she was helping. So right now, population density doesn't seem like a friend at all. An epidemic would seem like the one type of disaster where the social connection and social capital I mentioned in Episode 4 would hurt rather than help you.

But it's not so cut and dry. Epidemics tend to occur in clusters, so the risk to most people is distant exposure, that is, encountering people from a region where the virus has become widespread. Air and sea travel, we all know, have done a lot to spread the virus. Therefore, it seems to me that if your city is laid out so you have to travel long distances to meet your routine needs, the layout of the city itself will expose you to different population clusters.

That creates more opportunities for the virus to spread from one place to another. Think of the people who touched that gas pump or shopping cart and draw an imaginary circle around all of their homes. It's a large circle. In Edenicity, each city block is a lot more self-sufficient than they are in any modern city. This alone would slow long-distance spread of disease. Under a shelter in place order, I imagine the cafes would close their dining areas, but still deliver meals house by house within a block. There would be no gas pumps or grocery shopping, so again there's much less distant exposure. Some blocks would be hard hit, of course, but there would be very little opportunity for a virus to spread beyond them.

And once again, good design resolves a false dichotomy: the convenience that density provides versus safety.

▲ The sixth function of design

Let's go back to those factory farms I mentioned at the beginning. You know: the ones with all the noise and pollution that were supposedly the only things that could save us all from starvation? Do they sound like something that's gonna last?

Team Human's Rushkoff was amazed that even billionaires felt powerless to stop the world's biggest systems from ultimately crashing and burning. But are they—or we—really powerless? In Episode 5, I observed that the first function of design is to embody intention. The food systems of the world didn't just happen. They were designed, and they embodied the collective intentions of their creators. If these systems are becoming evermore inhumane, it's because their creators' intentions are based on inhumane assumptions. In other words, false dichotomies.

Not that I blame them. Most of us, if put in their place, would do no better because these same dichotomies are rampant in our culture. That's why so many revolutions overthrow despots only to prop up new ones. The purpose of design is not to identify bad guys and try to thwart them. We need to outgrow that infantile level of thought.

As I mentioned back in Episode 5, the second function of design is to identify and resolve false dichotomies. It does this by arranging interactive elements in space. That often has the effect of completely rearranging boundaries. Hmmm... maybe that's the sixth function of design!

Anyway, that's what we did today. Instead of thinking about the food system as out there on distant farms, we brought it in close to where we live. Instead of working small or working big, Edenicity does a lot of both where it makes sense. Zone 1 integral to our homes; Zones 2 to 4 at distances appropriate to their use.

▲ Close [music]

Now consider this: the Reference Design would easily support 500 million people in the United States—or a global population of 10 billion people. It would do this on 1.4% of the land, which is 97% less than we use now. Yet it wouldn't feel crowded because of how it chunks living space by desired degree of intimacy (I explained how in Episode 7). This lets us return 98.6% of the land to the wild again, while all 10 billion of us enjoy the security and delight of a garden to cafe lifestyle with the highest quality and abundance of food the world has ever known.

If you enjoyed Episode 11, please be sure to subscribe so you don't miss a show. You can download a copy of the Reference Design at edenicity.com. And please join me next time when I'll discuss the edenicity of transportation. I'm Kev Polk, and this has been Edenicity.

▲Sources

- GRAIN.org, Hungry for land: small farmers feed the world with less than a quarter of all farmland, May 28, 2014

- F.H. King Farmers of 40 Centuries. Organic Farming in China, Korea and Japan (1911; republished in 2004 by Dover)

- Douglas Rushkoff (2018) Survival of the Richest - OneZero

- Julia M. Simonetti, Economic Analysis of a Small Urban Aquaponic System Master's thesis, University of Florida, 2015.

- Joel K. Bourne, Jr., Aquaculture, National Geographic (retrieved April 8, 2020)

- Cities issue, National Geographic, April 2019.

- Brent Ladd and Julie Frankenberger, Management of Ponds, Wetlands, and Other Water Reservoirs to Minimize Mosquitoes, Purdue University Extension Water Quality newsletter, WQ-41-W. Accessed 2013-2020.

- Zoë Schlanger, Dirt has a microbiome, and it may double as an antidepressant, Quartz, May 30, 2017.